Charlotta Fredrica Serrurier (18 Feb 1823 – 29 July 1884)

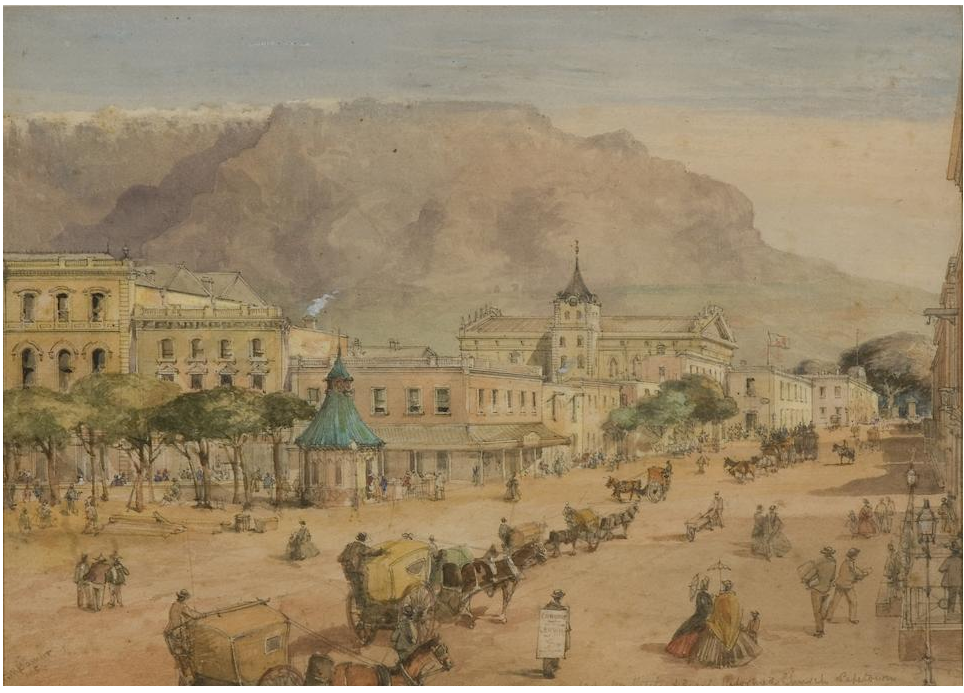

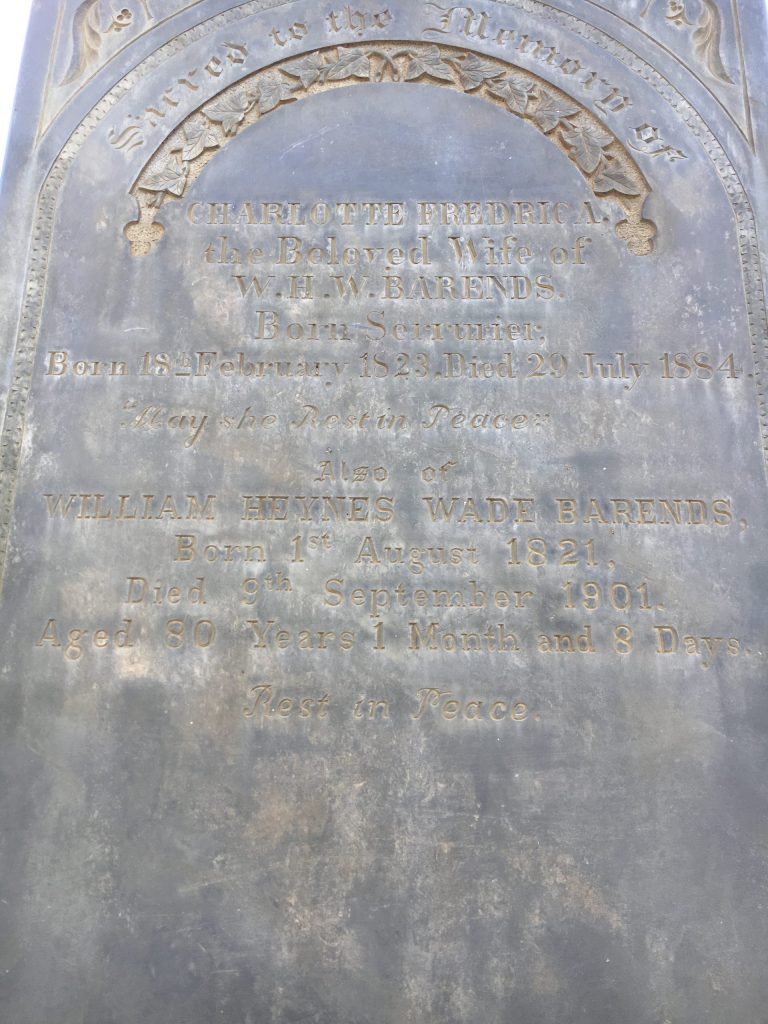

In researching my direct paternal ancestry, I had come across the gravestone of my 2x great grandfather Charles Samuel Barends (1848-1936) in the Dutch Reformed Cemetery below Groote Schuur Hospital in Cape Town. Or rather I found an image of the gravestone on the website of the Genealogical Society of South Africa. Fortuitously I was in Cape Town on holiday soon after, and found that the graveyard had recently been totally cleared of overgrown vegetation and drug-dealing vagrants (having been a no-go area for decades) and on the day I visited, I found the gate padlock broken open. And there I found not only Charles Samuel’s gravestone (broken in the tree clearances), but standing alongside, the headstone of William Haynes Wade Barends, and his wife Charlotta Fredrica Serrurier.

I thought I must have found another generation to add to my family tree – my 3x great grandparents. I knew of William Haynes Wade from a newspaper clipping in my possession, reporting on his funeral. At that stage I had no paper trail connecting father and son, but now the sharing of the plot and the existence of the clipping amongst the family papers seemed pretty conclusive. The tombstones gave me names and dates to research further.

Who was this Charlotta Fredrica Serrurier?

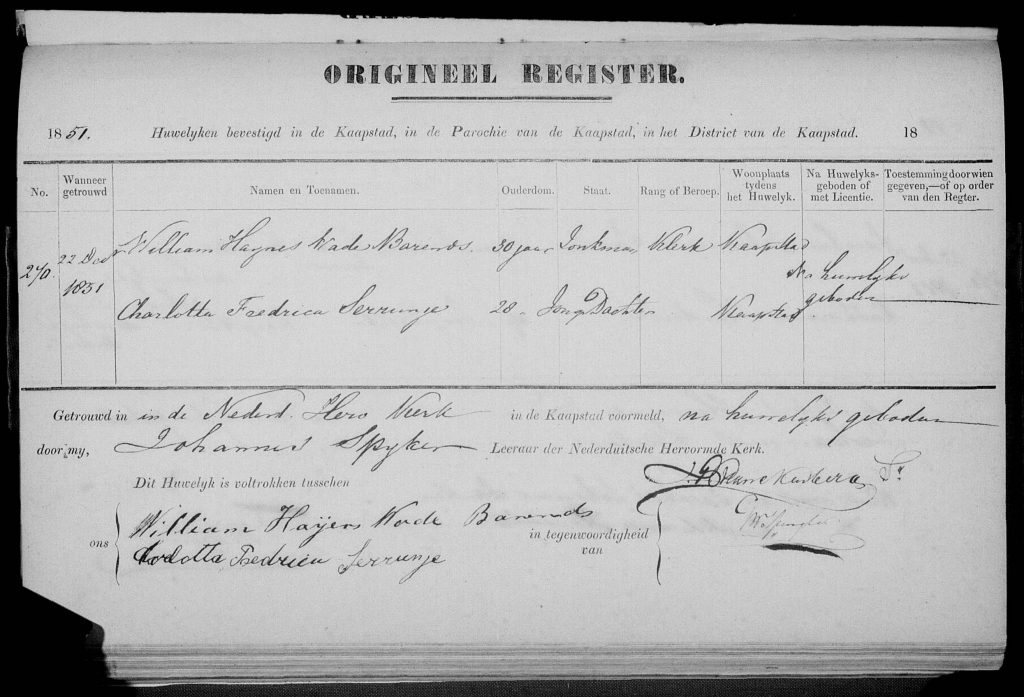

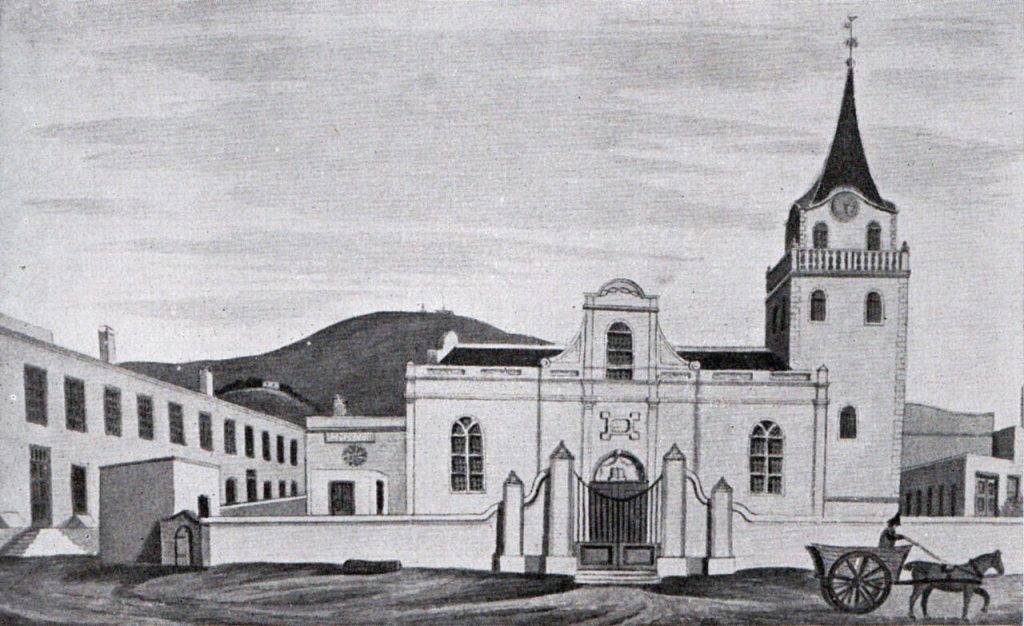

Using the names and dates on the gravestone, I soon found that she had married William Haynes Wade Barends on 22 October 1851 at the Dutch Reformed Church (1) – the Groote Kerk on Adderley Street in Cape Town, and I began to find baptisms of the rest of their family of ten children in all (of whom five survived into adulthood). Some were baptized in the Dutch Reformed Church, but I could not find a birth record for the person I assumed was her son, my great great grandfather, Charles Samuel Barends. And I could also find no records regarding her origins – in particular no baptism.

A little on-line research into the Serrurier name then revealed the remarkable body of genealogical research done by Dr Robin Pelteret on a renowned Cape Town Serrurier family. But a name on her gravestone alongside my 2x great grandfather was not enough to connect me and Charlotta to those Serruriers.

The “raven-haired beauty”

But then I read further in Dr Pelteret’s research, and came across an astonishing reference, regarding an unnamed “raven-haired beauty”, of whom no written records were known, but who was remembered within Serrurier family tradition. Dr Pelteret had heard the information first hand from an elderly Serrurier descendant in the 1980’s:

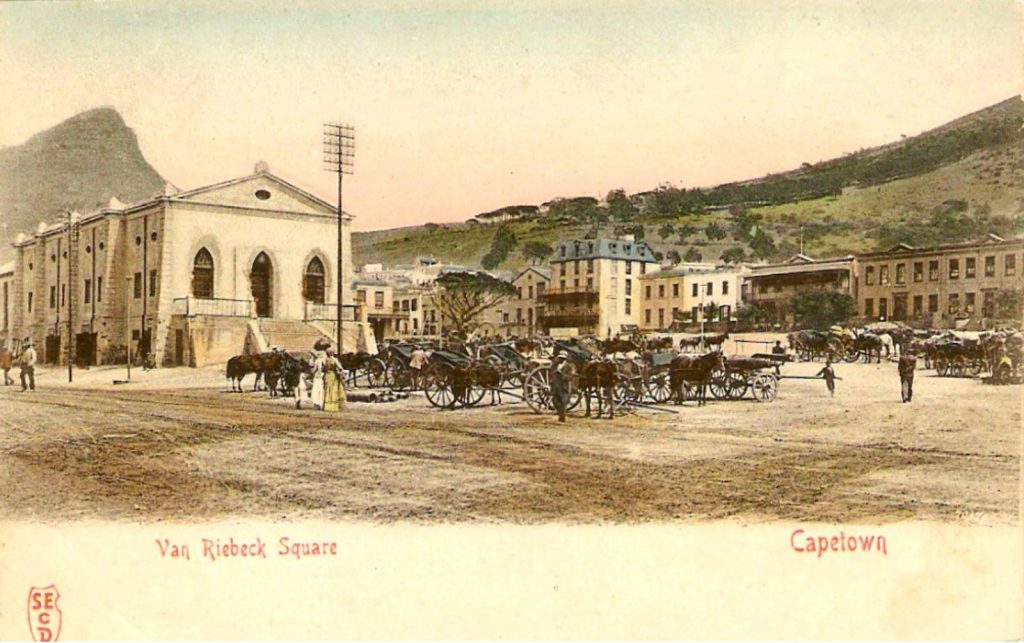

“There was rumoured to be a liaison between Petrus Johannes Denÿssen and an (undocumented) “raven-haired beauty”, the sister of Lodewyk (Louis) Serrurier Snr. (1816 – 1899)” … “The oral history relating to the sister is as follows: unknown female – said to have been an extremely attractive woman. Married beneath her social standing. He, a basketmaker, had his little factory in the basement of the St. Stephen’s Church, the “Old Theatre” or “Komediehuis” in Riebeeck Square, Cape Town. Later, she went on to live with Judge Denys of the OVS “after whom Deneysville is named” (sic). She produced 2 daughters : a daughter who married a “tobacco man”; and another daughter who married a tug-master known as “Captain”. The latter couple produced a daughter who reputedly married into wealth.”

I should recap what we already knew on the Barends side: my 2x great grandfather Charles Samuel had inherited a business from his father which occupied a basement workshop under St Stephen’s Church, Riebeeck Square for at least 80 years ending in 1930. Charles Samuel had taught himself coopering, but also produced traditional woven reed baskets and chair seats.

So with a shiver down my spine I realised the two families’ oral histories combined in that moment to identify the elusive “raven haired beauty” remembered by the Serruriers. She was without a shadow of a doubt Charlotta Fredrica Serrurier, daughter of Jan Fredrik and Charlotte Serrurier, and granddaughter of the founding father of the South African Serrurier’s, the Rev. Johannes Petrus Serrurier, the senior minister of the Groote Kerk in Cape Town for over four decades from 1760 to 1804.

I subsequently heard from Dr Pelteret that he had spent many hours in the archives trying to track down the nameless mystery sister, without success. The incredible co-incidence of our two oral histories colliding in this way was astonishing. Without Dr Pelteret’s record, I would have had almost no way of connecting Charlotta to her brothers and parents.

The Denyssen Connection

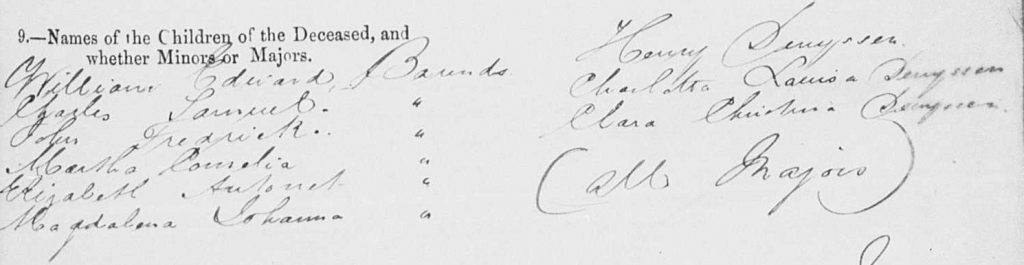

At almost the same time, I discovered the Death Notice of Charlotta Fredrica Barends in the Cape Archives, and this shed new light on the second part of the Serrurier family story. Alongside the names of her surviving children with William Haynes Wade Barends, were three other names: Henry Denyssen, Charlotta Louisa Denyssen and Clara Christina Denyssen.

Charlotta had not later gone off and married a “Judge Denys” – nor had a relationship (one hopes) with the Hon. Mr Justice Petrus Johannes Denyssen: in fact she had previously been married to (as I have since discovered) his younger brother Hendrik Justinus Denyssen, whose family included distinguished lawyers and indeed a judge. Her story had just become even more interesting.

And then there was the final twist. As told in an earlier post, a distant cousin sent me the baptism record he had found for Charles Samuel. And it was not from the Dutch Reformed Church at all – and it predated her marriage to William Haynes Wade Barends by 3 years. And no father is mentioned. Everything pointed to my 2x great grandfather not being a Barends at all.

But lets go back to the Serruriers and the Denyssens.

The Serruriers were a French Huguenot family who escaped persecution in France, fleeing to Hanau in Germany where my 5x great grandfather Johannes Petrus grew up, the son of Louis Serrurier, a protestant minister. To quote from Dr Pelteret:

He enrolled for theological training at Leiden University in 1753; and was ordained in 1759. He was appointed whilst in Amsterdam as pastor to the Dutch Reformed Church, Cape Town, and assumed duty in 1760. The family lived at 26 Longmarket Street and (anecdotally) at the corner of Venus (later Queen Victoria) and Wales Streets. He remained at the Groote Kerk for 44 years, and was revered for his powerful preaching skills. Duties of historical note include : burying Governor Tulbagh in 1771; conducting the inaugural service of an enlarged Groote Kerk and preaching the first sermon from the magnificent pulpit built by the cabinet-maker Graaf between August 1788 and December 1789 to a design by Anton Anreith; the dedication service of the Dutch Reformed Strooidakkerk, Paarl in 28 April 1805, and the pulpit in the Sendinggestig, Long St., CT. He retired in 1804, living an active further 15 years. The estate was valued initially at a substantial 293,600.18 rixdollars.

www.pelteret.co.za

As was not unusual in the period, he fathered a dozen or so children, of whom Charlotta’s father Jan Fredrik was number five. Along with his brothers, Jan Fredrik was sent to Europe for his education, and married his first wife Marie Jeanne Gosset in Amsterdam and had three children there between 1792 and 1797. Returning to Cape Town (possibly already a widower but accompanied by at least two of the children) he married Charlotte (surname unknown) and had at least four more children with her (2):

Lodewyk (“Louis”) Serrurier Snr (b 1816)

Samuel (“Alexander”) Serrurier (b 1818)

Charlotta Fredrica Serrurier (b 1823)

Johannes Petrus (“John Peter”) Serrurier (b 1823)

Jan Frederick had his fingers in various business enterprises, and owned 23 acres of what was later to be called “Fresnaye”. He lived at 12 Wale Street and died in Newstreet, Cape Town, a “Gentleman” on his Death Notice (3). He had meanwhile remarried twice and had at least one more child.

So Charlotta and her brothers would have grown up amongst the elite of Cape Town in the early days of the English Colonial administration. Her father was already 55 years old when she was born, wealthy, and a member of a large and well-known family. Her grandfather died just before her birth, and left a considerable fortune to her father, not to mention a highly respected name.

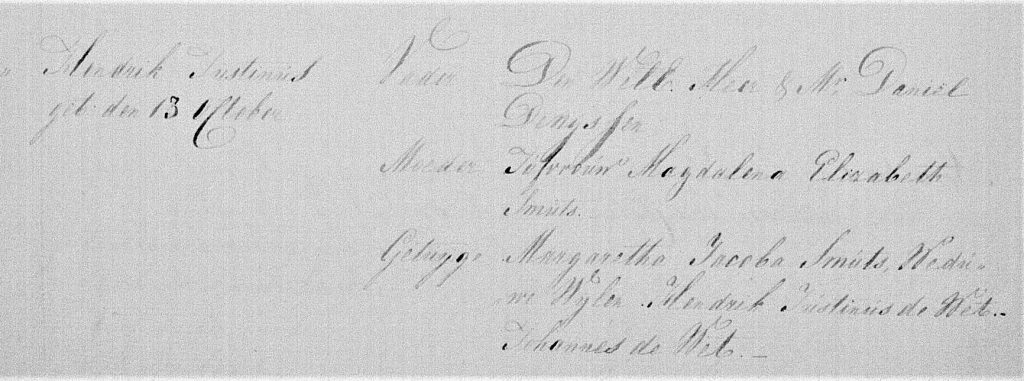

Around 1839, when she was just 16 or 17, she married Hendrik Justinus Denyssen. It seems theirs was a very suitable match between the children of two socially elite families. Henry was the son of Daniel Denijssen, a former Fiscal (or Attorney-General) who came out to the Cape from Holland, later practising as an advocate. Hendrik Justinus’ elder brother Petrus Johannes followed their father into law, studying in England, and later becoming a Judge.

Charlotta’s father and Daniel Denijssen were at least close business associates and probably friends (4). Daniel’s social position and connections were about as elevated as Cape Society allowed. One of the leading legal figures in the Cape, he married Magdalena Elizabeth Smuts, whose sister Margaretha Jacoba was married to Hendrik Justinus de Wet, the President of the Burgher Council at the Cape. As a widow, she was godmother to her nephew – and it was in honour of her husband that he was named Hendrik Justinus. The De Wets lived in what is now the Koopmans-de Wet House museum in Strand Street.

I say “married ”, but no record of the marriage between Henry and Charlotta has yet been traced and I cannot trace the baptisms of his children with Charlotta either. This is unusual for the period, but might mean that they attended the Lutheran or Methodist churches, whose registers are not available on line yet. It is interesting that their wedding would have taken place during the period of the Groote Kerk’s demolition and rebuilding, when services were held in the Lutheran Church. However, the three children born to the couple took his name, list their parents on their Death Notices (5), and it is extremely unlikely that a couple of their social standing would have had three children out of wedlock.

Where did it all go wrong for Charlotta Fredrica?

These were emotionally and physically demanding years for a young girl just emerging from her teens. An arranged marriage (probably) at age 16. Three children in three years between 1840 and 1844. Her mother dies around this time. Her father remarries and has a new baby in 1848, loses his third wife and then marries for a fourth time in February 1849, before dying in 1850. Her brother Louis lost no less than three wives between 1840 and 1850.

In the midst of all this, Charlotta gives birth to a son, William Edward Barends in 1847 whose baptism is as yet untraced, and then a year later she baptises a fatherless baby son, not in the Dutch Reformed Church to which her family were so intimately connected (and her grandfather had been the minister) but across the road in the newly established English Church of St George. (6) It is only three years later that she marries William Haynes Wade Barends, whose surname both those sons were to carry.

How and why did William Barends enter her life?

William is clearly not of her social class (or even race). His great grandfather was a German immigrant bricklayer who had married into the free black community. His grandfather Jan George in turn had married the daughter of a Swiss immigrant and a woman of Cape ethnic origin. And then his father Godlieb Andreas had lived for most of his life and had his children out of wedlock with a freed slave from Bengal, marrying her only on his deathbed. Godlieb may not have mixed with the Dutch settler elite, but neither was he in any way working class – he had once even been well-off. He was well educated, had an extremely elegant handwriting, worked in a clerical role, lived in a large well-furnished house, owned slaves and a couple of horses, along with a substantial book collection. However, he went insolvent at about the time of William’s birth, and it is not clear how well Godlieb managed after the insolvency, but he had five children and seemed to have brought them up respectably. (It is interesting that Charlotta’s uncle assisted with the administration of his insolvent estate.)

William Haynes Wade went to work for his uncle by marriage in a general store – Van Driel’s in Bree Street, along with his half-brother Haynes Wade Battersby (his mother’s eldest son from a former relationship). So he was in steady employment and had prospects.

Was he in fact a “basketmaker” as the Serruriers remembered? He certainly was. In a newspaper interview published in 1934 to mark his 84th birthday, Charles Samuel says: “My father was the first basketmaker in the town, the only one”. Later they employed the basket weavers and certainly by the time he died he had established a reputation as a well known and highly regarded General Dealer, and his son Charles Samuel later took over the business. Apart from coopering and baskets, he must have sold furniture, as he goes on to say “There’s nothing left here now … I have sold most of my antiques to Mr Rhodes …”

Why did Charlotte, an attractive widow from a very good family, marry William Barends? From this distance, it is impossible to know, and we can only speculate. The Serrurier legend (though wrong in so many respects) retains (as does all oral history) a kernel of emotional truth – she married “beneath her” and the shock value of that kept her story alive down five generations.

Did her husband abandon her and the children just at the time her father and mother died? Was she forced to find a man who would give her a home? Was her only hope to marry “beneath her”, a man willing to accept her children, and provide for her? Divorce was not unknown at the time, and it is possible that she divorced Hendrik Justinus Denyssen – but she remained in close contact with the children, and it is curious that such a powerful family within the legal profession would have allowed her this – unless Henry himself had run off first!

Or is the story much happier? Did she fall in love with William, bear his children and ultimately marry despite the social differences? And of course this begs the question, was William the father of the two boys born three and four years before their marriage? What prevented the couple from marrying earlier? Perhaps the divorce took a while?

Whatever the circumstances of the marriage and the birth of the two boys, the Barends, Denyssen and Serrurier families continued to have close ties, with various members of the family standing as godparents to the children, and then the grandchildren (7). So perhaps the social differences were not so great after all. Certainly, her two brothers were hardworking “shopkeepers” of a sort and probably respected William’s hard work and success.

What happened to Hendrik Justinus?

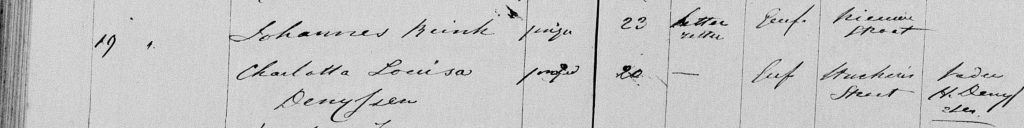

Before writing this piece, I had assumed the mostly likely explanation was that Hendirk Justinus had died after the birth of his 3rd child. But as I was writing this, I made another discovery. When Charlotta Fredrica’s daughter Charlotta Louisa marries Johannes Brink in 1863, she is under age (20 when age of majority was 21) so her marriage has to have her parents’ permission. On her marriage certificate, in the “by whose permission” column, it gives “by her father”, which I had assumed must mean William Barends as step father. But I have just found the original marriage banns record, where it says more explicitly that permission was obtained from “Vader H Denyssen”(8).

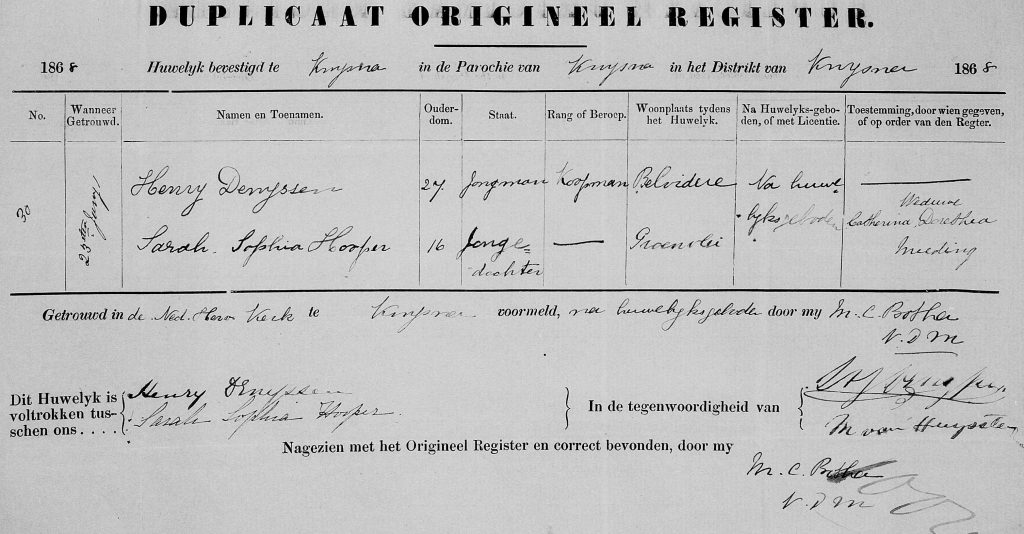

This seems to prove that Henry was still alive in 1863, but the children had lived with their mother in Stuckeris Street. So he must have divorced Charlotta Fredrica after all. He seems to appear again in 1868 as a witness to his son’s marriage in Knysna – the first name at “In de tegenwoordigheid van” looks to me like “HJ Denyssen”. (See further note 9 below.)

A Modern Family?

William provides a good home for Charlotta and her young family of five children, and together they have eight more, including four who died in infancy(10). And he gives his name to William Edward and Charles Samuel. Recent DNA evidence points to Charles at least being his son. Charlotta’s first three children keep their father’s name of Denyssen. In all Charlotta gave birth to at least 13 children, who in turn provided her with 66 grandchildren.

Charlotta’s eldest son Hendrik Justinus (or Harry as he has become) Denyssen marries an English girl in Knysna and has a large English speaking family – 14 children in all. Her Denyssen daughters marry into the old Dutch community, but her Barends children marry English settlers – one even returns to England with her husband and has a large family in London.

So we are left with an extended, and quite modern family, and interestingly one which was rapidly anglicising along with the whole Colony. And so Charlotta Fredrica Serrurier’s baptism of Charles Samuel in the English church of St George presages a sea change for this scion of the old Dutch Colony – and for the Cape as a whole.

Notes

(1) The French name Serrurier was often spelled in a Dutch corruption to Serrunje as here in the Marriage Register.

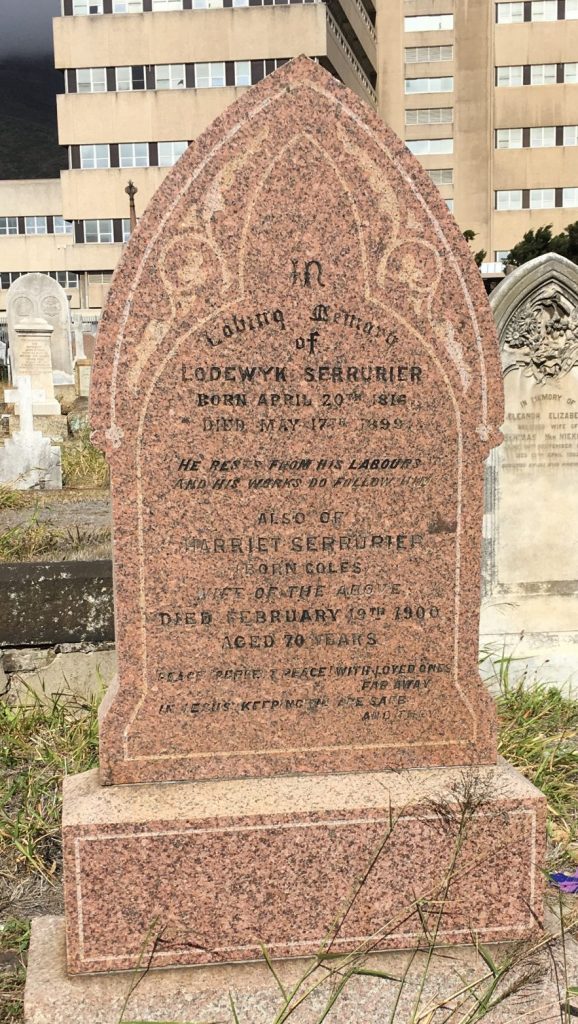

(2) Her brother Louis (note how all adopted English versions of their Dutch baptismal names) ran an immensely successful wagon and carriage making business in Keerom street (on the site of the current Supreme Court building) and made a fortune at the time of the Great Trek. He was later godparent to one of Charlotta’s daughters and left her a legacy. He is buried in the same cemetery as his sister.

Her brother Samuel Serrurier (“Alexander”) was sexton to the “Scotch Church” (St Andrew’s Church, Cape Town) in 1867. He was a well-known coffin-maker and undertaker but died impoverished: he was owed a good deal of money on plots he had purchased on behalf of clients in Woltemade Cemetery, Maitland and who died without settling their debts.

Her youngest brother John Peter emigrated to England and died in Devon unmarried as a civil servant in the Commissary Control Department

(all this information about the Serrurier brothers comes from Dr Robin Pelteret’s work)

(3) MOOC 6/9/51 No.287

(4) Both were Founding Directors of the South African Association for the Administration and Settlement of Estates in 1836 – the worlds first Trust Company. (Source: “The Cape of Good Hope Government Proclamations from 1806 to 1825, as Now in Force and Unrepealed; and the Ordinances Passed in Council from 1825 to 1839”)

(5) The younger Henry Denyssen’s Death Notice lists his father as Henry Justinus Denyssen and his mother as “unknown” scratched out and “Serrurier” inserted.

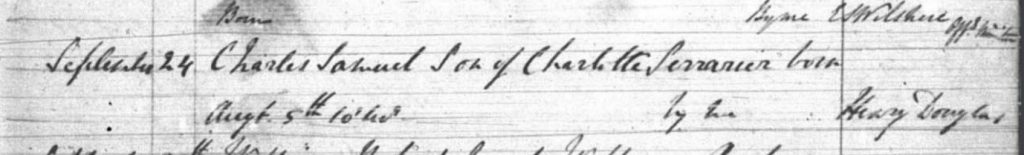

(6) The Baptism entry for Charles Samuel in St Georges is unusual. Where a couple is married the minister at that time would have recorded “Charles Samuel son of William Haynes Wade Barends and his wife Charlotta Federica Serrurier” (Women were always referred to by their born surnames in the Cape at this time, even after marriage, following a Dutch tradition). Where the couple are unmarried, but the father is known and acknowledged, the practice at the time was to write: “Charles Samuel, surname Barends, son of Charlotta Frederica Serrurier, reputed father William Haynes Wade Barends”. There are a number of examples of this in the same Register. Only where the father is unknown Or unacknowledged does the entry read like this one: “Charles Samuel, son of Charlotte Fredrica Serrurier”.

(7) There are many examples. Charlotta’s brother Lodewyk (Louis) Serrurier and Harriet Coles stood as witnesses to the baptism of Elizabeth Antoinette Barends in 1852 and Lodewyk Hendrik Barends in 1856.

In 1865, Charlotta Louise Denyssen and her husband Johannes Brink (from a family connected by marriage to the Serruriers in earlier generations) stood as witness to the baptism of William and Charlotta Frederica’s daughter Charlotta Johanna Barends (her namesake and half-sister).

In 1864, Charlotta Fredrica stands godparent to her grandson Daniel Brink, alongside “Henry Denyssen” – and this may be her son or her ex-husband!

In 1870 William Edward Barends stands godparent (alongside his other half-sister Clara Christina) to his niece Clara Wilhelmina Brink, daughter of his half-sister Charlotta Louisa Brink.

(8) Other entries for minors in the same register list permission given by for example “stiefvader”, “ouders”, “vader”, “grootmoeder” – so listing a name is unusual and stepfather would be listed as such. Her address however is Stuckeris St in what later became District 6, which was William and Charlotta’s address.

(9) There are a number of references to a Hendrik Justinus Denyssen in the Cape Archives which I have been unable to investigate due to the recent lockdowns. The most interesting is an auctioneers firm Van der Byl & Denyssen in the Swellendam district, operating in the mid 1840s – 1860’s who were responsible for the development of Malgas (Malagas) on the Breede River. There is a Hendrik J Denyssen who fathered a few children in the 1860’s in Knysna – who could be either the father or son. And there is another Denyssen family from Malgas with a Hendrik as the Paterfamilias who could be our Hendrik Justinus. Perhaps he too remarried and lived a new life.

(10) I have found baptisms for the following who I assume died young and are not listed in their parents will or Death Notices:

Lodewyk Hendrik (1856)

Frederick Alexander (1858)

Henrietta Wilhelmina (1860)

Charlotta Johanna (1865)